Despite being remarkably rare, extramammary Paget’s disease has subtly changed how dermatologists handle dermatological mysteries, particularly those that arise in intimate areas. It is characterized by reddish, crusty, slow-growing lesions that often resemble benign skin conditions like dermatitis or eczema. Because of this, many patients—who are frequently in their 60s or 70s—get delayed diagnoses, sometimes not receiving a proper investigation for their discomfort for years.

This uncommon illness has garnered attention in recent years from both clinicians and more general medical discourse. What distinguishes EMPD is its uncanny capacity to seem innocuous while concealing serious danger. EMPD, which is most frequently found on the vulva, perineum, and scrotum, can occur as a primary skin cancer or as a secondary symptom of a more serious internal cancer, such as prostate, bladder, or colorectal cancer.

Key Information on Extramammary Paget’s Disease (EMPD)

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Disease Name | Extramammary Paget’s Disease (EMPD) |

| Nature | Intraepidermal adenocarcinoma (rare skin cancer) |

| Common Areas Affected | Vulva, scrotum, perianal region, perineum, axilla |

| Age Group Affected | Primarily 50–80 years, with higher prevalence in females |

| Symptoms | Itching, redness, pain, crusty or scaly plaques, burning sensation |

| Type | Primary (originating in skin) or Secondary (linked to internal cancer) |

| Diagnosis Method | Skin biopsy and immunohistochemistry |

| Standard Treatment | Surgical removal (Mohs surgery or wide excision), radiation, chemo |

| Recurrence Risk | High—requires prolonged monitoring and follow-ups |

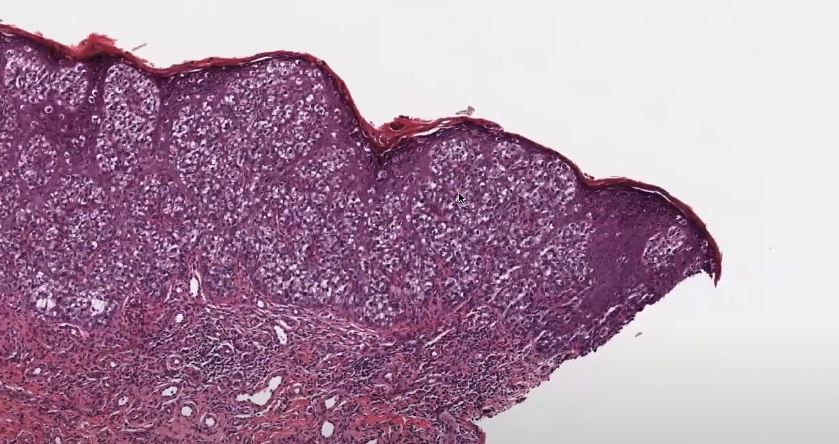

During biopsy, pathologists use sophisticated staining techniques to identify “Paget cells,” which are characterized by their large nuclei and distinctive, pale appearance. These cells are especially instructive. Their existence validates the diagnosis, particularly when paired with indicators such as CK7 and GCDFP-15. Staining patterns frequently alter when EMPD is secondary, assisting medical teams in identifying its actual cause. That degree of diagnostic accuracy is incredibly useful in directing suitable treatment strategies.

Additional hints have been discovered by genetic research in the last ten years. EMPD cases have been found to have mutations in the ERBB2, PIK3CA, and TP53 genes, which may pave the way for targeted treatments. Like current practices in personalized breast cancer therapy, these genetic profiles may one day enable highly effective treatment plans that are also customized to the patient’s cellular composition.

Surgery is typically the first step in a patient’s treatment. The gold standard is now Mohs micrographic surgery, particularly for lesions with blurry borders. Surgeons can ensure complete tumor removal while maintaining healthy skin by removing thin layers of tissue and monitoring it in real time. According to studies, recurrence rates are significantly reduced with Mohs surgery, going from over 30% with traditional methods to almost 23%.

Alternative therapies are useful for people who are unable to have surgery because of other medical conditions or personal preferences. The use of topical medications like imiquimod, radiation therapy, and even laser resurfacing procedures is growing. These non-surgical procedures can be especially helpful in superficial cases, providing both cosmetic improvement and symptom relief.

The clinical profile of EMPD is only one aspect of its complexity. This illness affects very private social and emotional domains, which could cause delays in diagnosis. Especially in older populations, many patients are uncomfortable talking about symptoms that affect their anus or genitalia. That hesitation makes sense, but it’s risky. A lesion that is written off as irritation one day might turn out to be invasive carcinoma the next.

It’s interesting to note that public figures and celebrities have been contributing more to discussions about skin conditions. Even though a celebrity diagnosis of EMPD hasn’t made headlines yet, the general cultural movement toward body positivity and health transparency, which was spurred by celebrities like Khloé Kardashian and Selena Gomez, has made room for candid discussions. Routine screening and early detection may become much more accessible in this new environment.

Gender dynamics in healthcare are another area where EMPD has social ramifications. Although women are more likely to be impacted, men are also significantly affected, especially those in East Asian nations. In both groups, open discussion about personal health is frequently discouraged by cultural norms. Clinicians may promote early detection and better results by incorporating EMPD education into general healthcare literacy initiatives.

EMPD treatment requires close coordination between medical teams. In order to make sure that every suspicious area is checked and every treatment option is thoroughly investigated, dermatologists, oncologists, gynecologists, and radiologists frequently collaborate. This kind of interprofessional cooperation has been especially beneficial for patients with invasive EMPD, which can spread to visceral organs or lymph nodes.

For example, sentinel node biopsy has become a vital tool for lymph node evaluation. Doctors can act sooner and more confidently if they can determine whether cancer has spread. Nowadays, staging systems like Hatta’s N0–N2 framework are frequently used to monitor long-term results and direct treatment intensity. Patients with bilateral or distant lymph node involvement who are staged as N2 need closer monitoring and more aggressive treatment.

After treatment, continued care is essential. It is common for EMPD to recur years or even decades after it was first removed. This perseverance necessitates a strict follow-up plan. Check-ins every six months for the first few years are usually advised for non-invasive forms. Quarterly assessments are more suitable when invasive or metastatic disease is involved. Depending on where the initial lesion was, these could involve pelvic imaging, colonoscopies, cystoscopies, and skin biopsies.

Technology is also beginning to influence the management of EMPD outside of the medical context. Diagnostic tools driven by AI are developing quickly. Machine learning models trained on images of skin lesions may eventually identify EMPD in its early stages, much like facial recognition aids in the identification of rare genetic disorders. That’s especially creative for patients who are reluctant to see a dermatologist or in rural areas. In a longer diagnostic chain, these digital tools might be the initial warning sign.